In the ever-evolving relationship of the museum with the moving images, it seems like The Forbidden Room has brought us a new proposition. Cinema has staged the museum numerous times, perhaps most iconically with the three young people running through the Louvre in Godard’s Band à part (1964). From a cinematic object, the museum later became also a guardian and a vault of cinematic images, while also trying to present new ways of exhibiting moving images through installations and all of its iterations.

Well, not only now does the museum replace theatres and screening rooms, it also is taking over the business of being a stage for film. Indeed, Guy Maddin’s latest creation, co-directed with Evan Johnson, has been shot in one of the cathedrals of modern and contemporary art, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, along with a multi-cultural space in Montreal, the PhiCentre. In both places it was produced in public, before groups of wandering museum visitors or flâneurs typically avid for performance art, which by default The Forbidden Rooms became (one of several things). But unlike Godard’s film, it offers its space not as itself, the museum, but as a classic movie studio where to build a set.

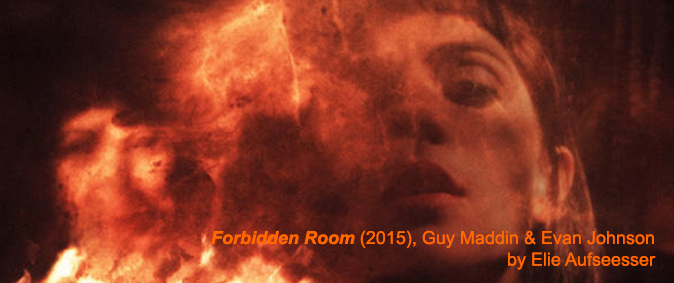

With the traditional cinema economy not welcoming a project of this nature, The Forbidden Room takes refuge in this new meadow. Adding insult to injury, the directors create another type of infidelity: from its opening credits, it seems like there is a desire to burn the celluloid. From one title card to the other – a sort of history of title cards graphics – the film burns for a split second, until we realize it was simply morphing into the next one. Not only is it burnt, but also attacked by fungus, unstable, untrustworthy. Paradoxically, what allows that to happen is precisely the fact that this movie is not physical material, but only digital. Indeed, the whole movie is shot digitally, though it fights very hard not to let it show. The directors take this paradox one step further, adding film-like effect to transitions that are only doable in digital platforms.

Hence, this is precisely one of the contradictions that Guy Maddin and Evan Johnson’s latest film stages: if these images blend into one another so organically, it is through their inorganic nature. But what do they consist of exactly? Apart from the credits, The Forbidden Room opens with an educative film, written by John Ashbery, on the pleasures and habits of taking baths. Closing the film with that same setting, this segment loosely undertakes the role of a framing narrative for the rest of the movie. Just as Maddin’s previous feature film Keyhole (2011) was about characters peeping through, well, a keyhole and getting lost in it, the camera here dives into the bathtub’s drain, down to the abysses of the ocean. There, another story begins, this time in a submarine, and then another story will be triggered through one of the characters, and so on and so forth. These short narratives are interwoven together, through which we work to find a guiding thread, with mixed results (on which we’ll come back later).

As much of his past work testifies, the Canadian director is constantly in search for a look that is of another time, a scent of something that is no longer around. A ghost, an ectoplasm. Is cinema as a whole an odor that one will not be able to smell anymore? The least we can say is that this film certainly takes part in this eschatological discourse happening in academic circles (and to a smaller extent in film criticism), through a “poetic of obsolescence” (to use an expression penned by Thomas Elsaesser), a restaging of a fantasized (fetishized?) past aesthetic. Everywhere the directors look, there is this sense of lost. The stories are pretexts to the real subject of the film: images. How to find them again? Characters are in search of their past, and so is the movie, who loses itself in the vintage aesthetic already mentioned, summoning different genres (satire, adventure, monster movie, melodrama, John Ashbery, Jules Verne…) on a semi-narrative, semi-experimental mode. At first Cesare (Roy Dupuis) erupts in the aforementioned submarine and triggers a flashback of his quest for his love, Margot (Clara Furey). At first, it looks like we will peregrinate through the narratives with Cesare, but soon enough we are left alone, having to juggle between a set of stories that, by virtue of them being put together, have a common thread. However, the latter is not to be found in the linear or even fragmented tales, but in this mission described in the biblical quote opening The Forbidden Room:

“When they were filled, he said unto his disciples, gather up the fragments that remain, that nothing be lost.” John 6:12

This fear of loss seems to be at the heart of the process as much as the movie itself. Coming across a catalog of lost movies, Maddin took over the task of directing a number of them. Haunted by the fact that 80% percent of silent era films (figure provided by himself) are gone forever, he selected old productions to remake based on full scripts, storylines or simply a title. In a typical cinephilic impulse, he claims that the more he read about them, the more he wanted to see them. He then shot one story a day, in the environments mentioned earlier, between Paris and Montreal.

This gesture realizes, so it seems, a number of fantasies:

They do what an archive director cannot do, but perhaps secretly dreams to do, namely go one step further than preserving (or even fixing), by bringing something back from the dead. There are a number of reasons to go for a remake: commercial value; homage; a sense of making the same, but better. Here, none of the above really applies. The commercial value is null (at least in classic distribution networks), it really isn’t an homage since no one could possibly know the referent, and there is no desire to improve an already existent film, since for all that we know it hasn’t existed in a long time.

There might be something akin to the motor animating found footage filmmaking. “At the heart of this process is the paradoxical cultural moment where to be retro is to be novel, where ‘going vintage’ is ‘avant-garde.’ Obsolescence and progress are the recto and verso of each other.”, wroteThomas Elsaesser, in The Politics and Poetics of Obsolescence. The Forbidden room is a new film, in the sense that it is a new release, that works to have us believe through its digitally-vintage look that we are seeing a film that has been once lost (and it was) but has been recovered (but it hasn’t). It stands somewhere between the strand of mockumentaries like The Blair Witch Project (Edouardo Sánchez, Daniel Myrick, 1999) and film of “actual” found footage, like those of Bruce Conner, Ken Jacobs or Gustav Deutsch. What it really asks us, the audience, to do, is to suspend disbelief. Call it found footage, appropriation art, classic remake… whatever it is, the most important is that we connect the dots within the object itself (which is often masterfully done by the artists just mentioned, expanding meaning beyond the practice of re-editing itself).

One image alone contains many potential narratives, and the power of montage films (perhaps “contrary” to transparent narrative), is to constantly make us aware of those. But the power of evocation is lost here, giving way to a clear desire for storytelling. With the choice of not taking the material they are re-activating totally seriously (there is a lot of goofiness, as always with Maddin), it becomes complicated for us to sign the spectatorial contract. Where his humor served the constant electricity in Keyhole, here it becomes just another obstacle in getting a hold on the proposition made to us. Rapidly, the connection between those subplots become blurred (purposefully so) and it gets increasingly harder to find the truth behind the layers of make-up, to the point at which we just shut down any intellectual effort, but without the evocative pleasure of a found footage film or even the fetishistic pleasure of seeing images that come to us after decades of drifting in the unknown. The film seems condemned to be a communicator of Maddin’s enthusiasm about cinema and moviemaking, not unlike a Quentin Tarantino, of whom he can be seen as an “experimental” pendant. Just like Tarantino, this condemns his films to constantly try to get over the top. This excess, however, also distracts from what the actual directing is doing, which again, hidden behind layers of effects, might be all too banal.

As we give up on the active work that such films demand (and that actually any film should require), we fall into another fetishistic game in noticing again the five stars casting, composed of famous Quebec and French actors (impressive list for whom is part of those two cultures). In a constant balancing between mock and homage (one not going without the other might be the moral of it all), the film systematically announces a character’s entrance with a title card stating their name as well as the name of the actor lending them their appearance.

The displeasure, however, makes us wonder: could have it worked with a more readable narrative, as a more generously welcoming or comfortable object? The title might be an indication. Like dreams, it is a forbidden place accessible only to one, and going into anyone else’s might be an impossible task.

Part of the answer is also in the process rather than the film itself. Indeed, the project’s inception is connected to an online interactive project called Séances, under the patronage of Canada’s National Film Board. It is unclear exactly how it will be presented, since it has yet to be launched, but from the explanations given by the directors, it seems like it is going to be a platform through which one will be able to navigate freely and interactively through those short remakes. Quite literally, there will be a number of online séances. The latter has in fact two meanings when put in relation with this film. One is the main French usage, which would be a showing or movie session, a screening in other words. The second, mostly used in English but also true in the language of Molière, is the gathering of a group of people to summon the spirits and ghosts from the past or the beyond. A programmatic title indeed, involving enchantment in both instances, and quite unlike a more hermetic forbidden room.

Whatever the details actually are, it sheds a light on the possibility that Maddin’s image-making drive might have been waiting for this medium all along. Keyhole explores the numerous fantastical rooms of a haunted house in very explosive manner and The Forbidden Room plays even less linearly and more with “clips”, who in turn leads to others in a pattern that is somewhat random (or esoteric enough that it is left to the spectator to decipher). This is not unlike the way of consuming online video platforms like YouTube, and the contemporary practice of constantly digressing. Drifting from a cat following a laser to a never-heard-of soviet animation film from the 1920s is now part of our daily routine. Whether it’s authentic or fake is secondary; what matters is the active gesture of editing or curating happening in the moment, motivated by curiosity, boredom and many other feelings, seemingly disinterested in any final or definite purpose. However, the narrative of loss and trauma is harder to sustain in the face of so much availability and the notion of “found” greatly diluted. It is only after this initial idea of Séances that the desire to make a film for the theatres (and the festivals) arose. This might explain this sense of inadequacy felt in the screening: one is a linearly edited object, stating right in its title its opacity; the other, though built out of the same material, is a digital upgrade of a classic individual screening.

One could argue that it is not relevant to speak of a project I haven’t seen yet. I would agree, if this film specifically did not inscribe itself in this cinephilic tradition that allows or even requires one to speak about, or make, films that were nothing but rumors. The impression lent by this screening at the New York Film Festival is that the humor and the goofiness was not at its place, that the stories were not at their places, that the actors were not where they should be, and even that the camera pointed in the wrong direction. However, all of that might come from the fact that the film itself might not be experienced in the conditions that it should be. This is perhaps Guy Maddin and Evan Johnson’s major Freudian slip, in that by wanting to show this film in the “cinema theatre” to prove its relevance (of the film as singular object and cinema as a dispositif), it actually states the growing irrelevance of a place where old movies used to live, and now go to die.